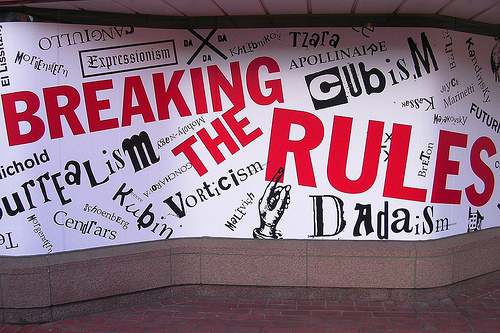

Rules are made to be. Are they?

I grew up at a time and in a system when obeying rules blindly was a question of survival for some, of belief for others, and of conformity for most. The arrival of puberty and democracy quickly taught me that rules should always be questioned, including the reasoning and authority behind them.

After all, rules are based on opinions or the subjective interpretation of (a selection of currently known) facts. So I have learned to rely on myself rather than what others tell me – with my basic set of rules unnegotiably defined by human rights.

Doesn’t make too bad a citizen.

manipulative?

And doesn’t active and democratic citizenship need citizens capable of critical thinking? People who are able to look behind facades, analyse nebulous motifs, locate hidden interests, and see beyond the obvious. People who appreciate that every rule was made in a specific context, with a specific aim – and may meanwhile very well be outdated, pointless or harmful.

Consequently, in our work we aim to empower young people and youth professionals to think critically – hoping to get a simple yet powerful message across.

More often than not, rules are made to be broken.

But the kind of critical thinking we hope to instill in people seems to be harder and harder to get out and get to. I wonder why?

«Critical thinking is important, because it enables one to analyze, evaluate, explain, and restructure our thinking, decreasing thereby the risk of acting on, or thinking with, a false premise.» (Source)

Take the example of simulation exercises in training. Usually, I design them in a way that the rules and restrictions are irritating and invite to be challenged. What makes each simulation unique and interesting is to see how different people challenge the rules and overcome the restrictions.

In recent years, the rules had to be harder and restrictions more tight to provoke people to break them. In recent months, I have experienced twice that people did not break any rule at all – and rather lived through the exercise, bored or frustrated, irritated or confused.

Now, I am the first one to admit that this very simulation is crap. In fact, it is. But nonetheless I wonder whether people are changing – changing away from self-confident critical reflection…

Rules are not used for guidance any more – they are obeyed. Blindly.

Tell me I’m wrong.

Comments

4 responses to “Made to be broken?”

Some interesting points you make there, Andreas. I agree with most, however not all. Rules, for me, are a way to reduce the complexity of life, which can be useful in some cases, in some not. When I drive a car thru the city I trust to that most people respect the rules to a certain degree (at least as much as I do) as this saves us all a lot of frustration and bills from the garage.

In my opinion people should not only have the ability to critically think but also the competence to make an informed decision on what is actually worth being questioned, discussed, debated and/or eventually thrown over. I’ve tried to discuss so many times with English people the sense of driving on the left side that I’ve come to the conclusion that spending that energy on traffic rules is just not worth it.

I see what you mean. But how can you make an informed decision on what is actually worth being questioned, discussed, debated and/or eventually thrown over – except by discussing, debating, and eventually throwing over?

Your example of traffic shows this quite well – you have come to your own conclusion through many discussions with the fans of left-lane traffic.

But your example also connects critical thinking to intercultural learning – rules are interlinked with their context, and if you behave in Cairo as you describe – obeying to the rules we are used to in relation to traffic – than you will end up sooner in an accident than you would think…

I have driven in Cairo and adapted my driving style to the local context (actually never had so much fun driving). I agree with you: rules and conventions are results of common experiences and dialogues a group of people in a certain context have and they have to grow, change and develop with the community itself.

I would even argue that critical thinking is one fundamental aspect of intercultural competence. Critically reflecting on ones own assumptions of what’s right or wrong, redefining them or reasserting them. Policy makers seem to have overseen this, somehow. Might just be too uncomfortable to lead citizens that are questioning everything one does…

Contemporary philosopher Alan D. Schrift — Professor and Chair of Department of Philosophy and Director of Center for Humanities at Grinnell College in Grinnell (IA), USA — adds a little depth to this discourse in an article on Eurozine entitled

«Questioning authority – Nietzsche’s gift to Derrida»