Why would a perfectly decent professor of education make such a radical statement?

Well, you may have noticed that learning styles have become very fancy these days.

“What’s your learning style? Find out in 2 minutes.” That’s just one of the slogans with which millions of websites and thousands of books try to catch the attention of whoever is interested in learning and education. A wide array of abbreviations such as MBTI, LSP, CSA, ASSIST, TSI or HBDI suggest scientific reputation and acceptance.

In the UK, the Government’s Department for Education and Skills (DFES) has picked up this steadily-growing trend and decided that all school students shall henceforth be categorised as either kinaesthetic learners (they learn by doing) or auditory learners (they learn by hearing) or visual learners (they learn by seeing).

I don’t know about you, but I have — in 25 years which I have spent in formal and non-formal education in different roles and capacities — not met one single person who is exclusively what the DFES calls a kinaesthetic, auditory or visual learner. Yet, in the UK this dangerous simplification is pushed forward by the so-called “Innovation Unit” of the DFES and widely supported by politics and administration.

On the website Teachernet, the education department provides 15 tips on teaching which caters the three learning styles – five tips for each of the three, containing hints like ‘practise active listening’ or ‘ask pupils to see words with their eyes closed’.

A leaflet-style ‘Quick Guide on Learning Styles’ for teachers and educators explains that there are a few common-sense ways of ‘diagnosing’ students’ preferred learning styles. One of them is called the IKEA-Test and goes like this:

Ask your pupils: If you buy something that you have to assemble when you get it home, do you:

a. open the package and try to put the item together without reading the instructions?

b. read all the instructions before you attempt to assemble the item?

c. hand the instructions to someone else to read them to you?

You may have guessed that option a. makes you a kinaesthetic learner, option b. a visual learner and option c. an auditory learner.

Congratulations.

Now, please don’t make the Obelixarian mistake (Ils sont fous, ces Britons!) and brush the British example aside. It is by no means a particular case, on the contrary: The UK just picks up on one of the most popular learning style theories around these days; the model is more commonly known as the VAK approach and widely used in and beyond education.

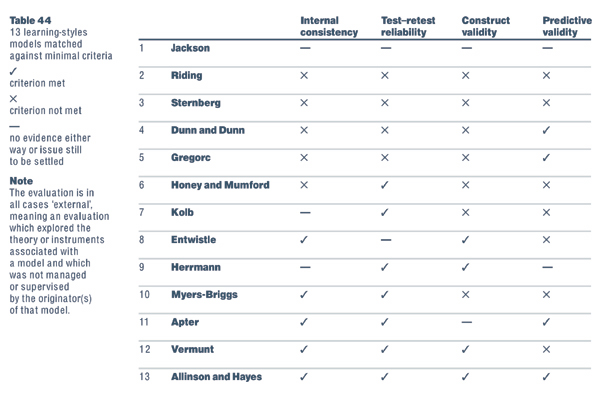

A research team led by Frank Coffield, Professor of Education at London University’s Institute of Education, has identified 71 different learning style theories and scrutinised the 13 most popular and influential of these in a major research project lasting 16 months.

The researchers’ assessment of the VAK model shows how dangerous and simplistic the pruning reduction to kinaesthetic, visual and auditory is. Professor Coffield says: “The real danger is that if learners are made to believe they are a kinaesthetic learner, they might see little point in reading a book or listening to anyone for more than a few minutes.”

While not all models promote such simplicity and ultimate one-sidedness, very often they are — deliberately or unintentionally — understood and (mis-)interpreted that way. One prime example is the reference publication of the DFES for teachers in the UK. As part of the series Pedagogy and practice: Teaching and Learning in Secondary Schools they published a 27-page booklet entitled “Unit 19: Learning styles”. Professor Coffield called upon the DfES to withdraw its publication: “The booklet is woefully uninformed about research. It is also impractical, patronising, uncritical and potentially dangerous to students.”

Two other models analysed in the framework of the same research — and using the same approach to ensure consistency — we all know very well: It is (1) Kolb’s Learning Style Inventory (LSI) and (2) the Learning Styles Questionnaire (LSQ) of Honey and Mumford. Both are frequently and enthusiastically used in non-formal education and referred to, amongst other places, in the Training Kits 1 “Organisational Management” and 6 “Training Essentials”.

Kolb has one category more to offer than the VAK-model: he divides learners into convergers, divergers, assimilators and accommodators. Honey and Mumford developed Kolb’s thinking a little further and identified activists, reflectors, theorists and pragmatists. Unlike Kolb, whose LSI basically asks people directly how they learn, their LSQ probes general behavioural tendencies rather than learning.

While Kolb’s thinking on learning styles certainly was the first and very important step in challenging the (then common) reduction of learning potential to one dimension, the instruments LSI and LSQ are both far away from being adequate to portray the reality of learning — a deficit they share with most other models and theories on learning which currently exist.

Or as Frank Coffield puts it: “This field suffers from serious conceptual confusion and a lack of accumulated theoretical knowledge.”

Yep.

The following table presents an overview of the analysis carried out by Coffield and his team, clearly showing that there seems to be only one model fulfilling even the most basic criteria (and the expectations raised by own claims, at that):

As you can see, the vast majority of currently (also in non-formal education) employed instruments to analyse learning styles and their underlying theories are seriously flawed.

Yet, let me suggest that we not only wrinkle our collective nose, shake our heads and laugh about the British government’s ludicrous attempts to address an increasing gap between learner’s needs and pedagogical responses in formal education, but that we also give ourselves the necessary push to be more critical and aware of current research.

The minimum we can do in appreciation of the work of Frank Coffield and his colleagues is to have a thorough look at Allinson and Hayes’ Cognitive Styles Index next time we would like to write about learning styles or we would like to use an instrument to analyse the learning styles of our participants.

At least.

Related documents

Learning styles and pedagogy in post-16 learning: A systematic and critical review (pdf, 1.2 Mb)

Should we be using learning styles? What research has to say to practice (pdf, 530 kb)

Quick Guide on Learning Styles – Leaflet (pdf, 170 kb)

DFES Booklet on Learning Styles – Unit 19 Pedagogy and Practice

T-Kit 1 Chapter 2 – Honey and Mumford (pdf, 170 kb)

T-Kit 6 Chapter 3 – Kolb (pdf, 520 kb)

Related Links:

Institute of Education @ University of London

Learning and Skills Research Centre

Learning and Skills Development Agency

Infed’s review and criticism of Kolb’s LSI

Wikipedia on Learning Styles

Wikipedia on current criticism of learning styles

Comments

9 responses to “Excuse, misuse or abuse?”

To read more, check out this article which was published in the Guardian in its education section, looking at learning styles as well: Article in the Guardian.

The article ‘Excuse, Misuse or Abuse’ raises some interesting points regarding learning style theory, highlighting the ineffectiveness (along with the dangers) of assessment methods which claim to categorise learners.

However, I believe the concept of different learning styles is a very valuable topic for students in post 16 education to encounter. Often they perceive education as a teacher-led activity; a syllabus and assessment-based process that is delivered and taught. To empower them with an awareness of learning styles is to open their eyes to the opportunity of achieving ownership, understanding and influence upon their own learning.

As a post-16 tutor, I find the VAK followed by the Honey and Mumford questionairres prompt excellent discussion, both on the results and the validity of the assessment process…students are very quick to identify flaws in the process, but are fascinated by the topic and issues that it raises. We explore other learning style theories and debate their relationship to topics such as personal development and adult learning theory. With a framework of ideas and experience to build upon, their engagement with education becomes inspired by their understanding that learning is not a passive event. Study skills become meaningful as they tailor approaches to suit their needs; empathy with their peers is enhanced through awareness of different approaches to thinking; in place of reactive disengagement, proactive requests for alternative delivery styles can be voiced.

Importantly, the students who particularly gain from the awareness of different learning styles are those with specific learning difficulties eg dyslexia. For these students, often already confused and frustrated by the demands of education, discovering alternative approaches to learning is vital.

Learning style theories must be used with care, as a platform for further investigation, but I find they are excellent at bringing the topic of learning into the curriculum to promote awareness, engagement and autonomy to the student learner.

Alison’s comment raises several very important points about the value of such approaches in actual teaching / learning situations. While I tend to agree with the original article that political and financial expedience and other “authority” led interests increasingly influence the quality of educational provision or a lack thereof, I nevertheless also agree with the idea that such tools can have educational value when used with moderation, intelligence and as part of a wider learning process, one

which critically engages the learner in their own learning.

One of the teachers interviewed for the Guardian article puts it very nicely:

I find this approach, in my interpretation commensurate with that of

Alison, interesting as it is both pragmatic and in it’s own way critical. It says so what if the theory is flawed, with the right approach in practise you can achieve interesting results even if the tool is flawed.

Nevertheless, what the original article does highlight and importantly so, is that educators and education policy makers are woefully underinformed about the relevant current research relevant for informing our practical work, and that we do not enough take the results of research into account when designing educational programmes. It also highlights that intelligence and discernment are not the always the main strengths of the people who are responsible for putting into practise the promises made by

politicians during election campaigns (one of the few occasions education policy surfaces as an issue of public interest or debate).

In my practical observation, and while research is considered one of the cornerstones underpinning the non-formal education field, practitioners are often disturbingly anti-intellectual and anti-academic. Researchers are very often guilty of not taking the practitioners seriously because they are concerned with less philosophical issues and because more often than not they are very caught up in their own research concerns and cannot or do not want to look beyond them. And the policy makers seem only to be worried about making the budget balance out with the even smaller amount

of money they have to use for more and more things and with meeting

targets set by politicians. Never the twain shall meet, so to say!

For me all this explains some of the blind reductionism that Andreas and Frank Coffield bemoan, even if it by no means exonerates it. If you ask me, we are dealing with a systemic problem. It will take political will and input from all three corners of the triangle, a big dose of cooperation and a lot of time and money (sorry – all these are sorely lacking at both national and European level) for educational thinking to evolve as radically as would be necessary to overcome the horrible tendency of direct cooptation of trendy theories into educational programmes.

For the moment, however, and here I air my own brand of

pessimism, I do not see more than a bit of tinkering here and there.

Having taught Parenting , a course in Family Studies , I have seen the variety of learners described here and needed to work closely with the Learning Strategies Dept. in the school for ” Special Education . ” I think that in a general sense it helps to employ VAK for appropriate lesson modifications . I recall asking the class ” Can you see that a newborn baby needs alot of attention ?” to realize one of my IEP students was literally trying to see a baby . She couldn’t think on an abstract level . So when it came to the 10 questions in the textbook about cribs and safety , I watered down the assignment for her , having her draw the crib in the text and label it . Then I had her explain to her peer tutor what each part of the diagram was supposed to do . And that became her way of getting through this assignment . This example also demonstrates the shortcomings of VAK . She was a visual learner , an auditory learner , and kinaesthetic , could likely assemble a toy crib . But she had an underlying learning disability in that she took everything litteraly unable to think along an abstract plain . She never made that leap . So , after this experience , I became very conscious of the language I was using . If I said ,” Do you see ” , I made sure that there was something to see .

In my opinion , a teacher needs to understand VAK when assigning work and when setting up group work . Good to arrive at common outcomes through varied approaches . So VAK allows for the enrichment of activities through varied means . Suppose you were planning a class activity such as Cafe Francais for your FSL students . And all of your classes would be contributing to this effort . You would seek out your visual learners ,show them pictures about France or Quebec and brainstorm some of the stuff they could draw to create their own setting/ nuance , for the event . Let your kinaesthetic learners build the sets . And work with your auditory learners in using their knowledge of French to welcome parents and staff to the event . And this way everyone makes their contribution to the event in a way appropriate for them based on the kind of learner that they are . In the world of adult education , one would need to make the leap from pedagogy to andragogy and the challenge would be to figure out what the kind of learner your student is . And then you would need to modify the course delivery system to suit that kind of learner . And this presents a particular challenge for anyone in the field of Adult Education .

In August 2006, Will Thalheimer offered 1.000 US Dollars to the first person or group who can prove that taking learning styles into account in designing instruction can produce meaningful learning benefits. So far, Will hasn’t had to pay…

In 2002, James Atherton wrote an article over at Heterodoxy entitled Learning styles don’t matter.

In July 2005, Catherine Howell described at Educause why steam came from her ears when reading about learning styles.

Oh, and Clark Quinn in June 2007 as diplomatic as it gets: rubbish.

Just so you know.

And here is where it gets really, really wild:

Read more here.

The discussion picks up momentum again — now it seems that some people are settling for learning styles not to exist; and call for teachers and educators to refer to the modality of the content for deciding how to teach and educate.

Stephen Downes has picked this up here, and as I commented there:

Harold Pashler, Mark McDaniel, Doug Rohrer, and Robert Bjork (2008) Learning Styles; concepts and evidence. In: Psychological Science in the Public Interest Vol 9 No 3.

Available on-line at http://www.psychologicalscience.org/journals/pspi/PSPI_9_3.pdf

Accessed January 3, 2010

James Atherton’s blog links to another nail in the learning styles coffin.

As previously noted, many of the most popular “learning styles” techniques are more or less worthless by any rational measure – and the most effective are rarely discussed.

And finally, the DTLLS and GDTLLS Blog says it out aloud as well: Learning Styles are “Bunk”!